Twelve String Power

by Michael Simmons

Acoustic Guitar, Nov. 1997

The origins of

Twelve String Power

by Michael Simmons

Acoustic Guitar, Nov. 1997

It's difficult to imagine what popular music would sound like without the 12-string guitar. Some of the most pervasive music of the last 60 years owes its power to the distinctive sound that Pete Seeger described as “the clanging of the bells.” Songs like “Goodnight, Irene,” Rock Island Line,” “Walk Right In,” Stairway to Heaven,” “Turn! Turn! Turn!” and “Hotel California” show what an important color the 12-string is in the sonic palette of 20th-century guitarists. Musicians as varied in style as Melissa Etheridge, Pete Seeger Leo Kottke, Leadbelly, Roger McGuinn, George Harrison, and Willie McTell have all made the 12-string an integral part of their music. In this article I'll trace the development of the modern 12-string up through the players and makers who are guiding the instrument through the ‘90s.

Origin of the Species

The modern 12-string guitar made its first appearance in America just before the turn of the century. The name of the first luthier to double the strings of a standard six-string guitar is unknown. There are two theories about his background.

The first is that the 12-string guitar was developed by Italian luthiers laboring in the guitar workshops of companies like Oscar Schmidt, Harmony, and Regal in New York and Chicago. Italian music has a long history of wire-string, double course instruments like the mandolin and because many of the builders were of Italian descent, it would be a natural experiment to double the strings of a standard six-string guitar. One of the most famous 12-strings in the world has a strong Italian connection. According to family legend, Leadbelly custom-ordered his famous Stella 12-string from Fulvio Pardini, Who worked for the Oscar Schmidt company in New Jersey.

The other theory is that the 12-string arrived in the U. S. from Mexico. Latin America has a long history of double-course variants of the standard six-string guitar. These include instruments like the tiple, the charango, and the cuatro. Mexico has a particularly large number of guitar variations ranging from the diminutive guitarra de golpe to the massive guitarrón.

In the U. S., the Idea that the 12-string is a Mexican instrument is an old one. A Lyon and Healy catalog published circa 1905 lists three models of “11- and 12-string guitars (Mexican style).” The Mexican designation was used to distinguish the double-course guitar from the “12-string bass guitar,” which was a form of harp guitar. It is curious that the catalog mentions two models of 11-string guitar but only one 12-string. From the description, it appears that the 11-string guitar was based on a seven string guitar with four doubled basses and three single trebles.

To further muddy the already murky waters of early 12-string history, there was a company in New Orleans called Grunewald that made a double-course guitar in 1904. Its catalog pictures a 12-string guitar described as “The Grunewald Harp-Guitar: A New Invention!” which has “Twice the Tone of any Guitar.”

Regardless of who invented the 12-string guitar, it was considered

something of a novelty instrument if it was considered at all. Except for

a very occasional custom order, the more prestigious makers like Martin

and Gibson left the 12-string market to the low-end builders. This is a

strong indication that the buyers of 12-string were at the poorer end of

the social scale. Indeed, many, if not most, of the early recordings of

12-string guitarists are of blues musicians in Georgia and Mexican

tejano

musicians in Texas. It appears that the first musicians to take up the

12-string were street performers. They were probably drawn to the extra

volume the double strings added. Because the doubled strings had such a

full, rich sound, a busker could work without other musicians and keep

all of the proceeds.

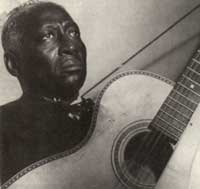

Willie McTell’s Blues

One

of the best early players to exploit the power of the 12-string was Atlanta

guitarist Blind Willie McTell. Atlanta was the center for the Piedmont

blues, a ragtime-based guitar style noted for its complex fingerpicking

and driving bass. McTell was one of the most accomplished guitarists in

a company that included players like Blind Boy Fuller, Blind Blake, Reverend

Gary Davis, and fellow 12-string guitarist Barbecue Bob.

One

of the best early players to exploit the power of the 12-string was Atlanta

guitarist Blind Willie McTell. Atlanta was the center for the Piedmont

blues, a ragtime-based guitar style noted for its complex fingerpicking

and driving bass. McTell was one of the most accomplished guitarists in

a company that included players like Blind Boy Fuller, Blind Blake, Reverend

Gary Davis, and fellow 12-string guitarist Barbecue Bob.

McTell was born blind in 1898 in Thompson, Georgia, but he never let his lack of sight slow him down. He traveled extensively throughout America, almost always by himself. He was able to navigate New York's subway system, thread a needle, and sew, and read Braille. McTell came from a musical family and he quickly took to the guitar and was soon playing at jukes, restaurants, and local parties. Sometime around 1922 he stopped playing guitar and started attending Georgia's school for the blind. Apparently the calluses from playing guitar impeded his ability to learn to read Braille. In 1927, he took up the guitar again, this time choosing the 12-string for which he became famous.

From that time on, McTell supported himself and his wife by playing music. He started making records, many under pseudonyms like Georgia Bill, Hot Shot Willie, Barrel House Sammy, and Pig ‘n’ Whistle Red. He was able to fully exploit the range of the 12-string and bring out new tonal colors. He could emulate the syncopated rhythms of a ragtime piano on a tune like “Georgia Rag” and recreate a rail journey on “Travelin’ Blues,” complete with bottleneck train whistles.

Although only a few photos of McTell survive, it appears he played guitars

made by Stella. Stellas were made in New Jersey and sold through catalogs

under a variety of names. They were favored by early 12-string players

because although they were inexpensive, they were well made and stood up

to the extra tension quite well.

Lydia Mendoza

In Texas the 12-string was one of the instruments being used by Mexican-Americans as they began to create a musical identity in their new country. One of the early stars in this new style that came to be called tejano music was Lydia Mendoza.

Mendoza was born in 1916. Her parents were refugees from the violence of the Mexican Revolution and worked in America as wandering musicians. By the time she was seven years old, Mendoza was proficient on guitar and mandolin. When she was twelve, the family went to San Antonio to answer a newspaper ad looking for singers. Lydia Mendoza made her first appearance on record in 1928, singing and playing mandolin with her family. They were paid $140 for 20 songs. They used the money to move north to work in the sugar beet fields of Michigan, but the family soon returned south to San Antonio.

The Mendozas found work playing in the huge open-air produce market. By this time the teenaged Lydia had started playing 12-string guitar. The family discovered that Lydia, with her powerful voice and striking good looks, was making more money when she sang solo than when she performed with the family. Word of the young singer reached Manuel Cortez, who ran a Spanish language radio show, and as her popularity grew she was asked to record again, this time as a solo singer.

Mendoza’s first solo record (and first hit) was “Mal Hombre,” a powerful

song about an evil-hearted man who leads a poor girl astray. She learned

the lyrics from a chewing gum wrapper. Her records of hard times and broken

hearts quickly became popular throughout the Southwest and Mexico. She

never forgot her roots, and she would often sing for the poorest farm workers,

thus earning her the name La Cancionista del los Pobres (the Poor People's

Songstress). Lydia withdrew from performing in the late ‘30s to raise a

family. She returned in the early ‘50s, and her career continued to prosper

as if she had never left. She continued to perform until her retirement

in the ‘80s.

Mexican-Americans were not the only guitarists in Texas attracted to

the 12-string. Sometime around 1912, a young Huddie (“Leadbelly” Ledbetter,

who was traveling with an even younger Blind Lemon Jefferson, purchased

a used Stella 12-string in a Dallas pawnshop after hearing one played by

a musician in a medicine show. The young guitarist took his new instrument

to a party that very night. His description of his entrance at that party

was also his challenge to the world: “ I put my foot on the doorstep and

my finger on the strings and said, ‘Here’s Leadbelly.’”

It is very rare that the music of one musician so defines an instrument. It is not an unreasonable statement to say that without Leadbelly the 12-string guitar would have faded into obscurity. The rural style of the early blues player like Blind Willie McTell was being replaced by newer urban sounds. In Mexican-American music, guitars and mandolins were being replaced by accordions and brass band instruments. Without Leadbelly championing the 12-string in the ‘30s and ‘40s, it probably would have passed into the historical curiosity category along with harp guitars and bass mandolins.

The outline of Leadbelly's life is familiar, with many parts reaching the status of legend. He was born in Louisiana in 1888 on a small farm. As he grew up he learned to work hard and also play hard, getting into the first of many run-ins with the law while still a teenager. He supported himself as a farmworker, cotton picker, and cowboy. Along the way he learned to play the piano, concertina (which he called a “windjammer”), mandolin, and guitar.

In 1917, Leadbelly was convicted of murder and sentenced to thirty years in the Shaw State Prison Farm in Texas. With his ability to work hard and make music he became a popular prisoner with guards and convicts alike. In 1923 the governor of Texas, Pat Neff, heard Leadbelly perform on a tour of the work farm. Leadbelly wrote a song asking for a pardon, and in 1924, in one of his last acts before leaving office, Neff pardoned Leadbelly.

Although he was now free, Leadbelly couldn't manage to stay clear of trouble, and in 1930 he was back in jail, this time on assault charges. He was sentenced to ten years of hard labor at the infamous Angola Penitentiary in Louisiana. Life in Angola was brutal, and after a failed escape attempt Leadbelly cast about for a legal way to get out. He applied to the parole board to commute his sentence.

At the same time a folklorist named John Lomax was looking for musicians who knew old-time folk songs. Lomax thought that the prisons, where convicts would be less affected by the changes in the outside world, would be the best place to look. He contacted the warden at Angola, who introduced him to Leadbelly, and the lives of both men were changed forever.

In Leadbelly, Lomax found the repository of folk song he songs looking for and more. Leadbelly seemed to be able to remember almost every song, field holler, and dance tune he ever heard, and he was a powerful and charismatic performer. Leadbelly hooked up with Lomax in what turned out to be a complex and controversial relationship.

At first Leadbelly and Lomax got along fine. Leadbelly worked as a driver, assistant, and liaison between Lomax and local African-American communities on Lomax's song collecting trips in the South. They later went north, where Lomax gave lectures and Leadbelly played his songs. These lecture/concerts were for the most part given in academic settings like colleges or scholarly conferences. Then they hit New York.

The story of the convict who sang his way out of prison was too good for the newspapers to pass up. They jumped on the story, and overnight Leadbelly was the subject of sensational headlines like “Sweet Singer of the Swamplands Here to do a Few Tunes Between Homicides” and “Murderous Minstrel.” Concert and movie offers poured in, but Lomax and Leadbelly were unprepared for the notoriety and soon had a falling-out over money.

Leadbelly tried playing for black audiences, but there was very little interest. A big show was set up at the Apollo, but it was a disaster. The sophisticated urban crowds were just not interested in hearing old-fashioned rural blues and folk songs. Although he couldn't succeed in Harlem, Leadbelly found a new and unexpected audience in Greenwich Village. The work of John Lomax and his son Alan had sparked an interest in folk song among the leftist intellectuals, and Leadbelly was lauded as a living treasure. Leadbelly became a star of the prewar folk scene. His songs were recorded by the Library of Congress and by Moe Asch, who later started Folkways Records. Songs like “Fannin Street,” “Midnight Special,” and “Rock Island Line,” were studied and performed by aspiring folksingers. In May of 1949, Leadbelly was diagnosed with Lou Gehrig's disease, and six months later he was dead. A year later his song, “Goodnight, Irene,” sung by the Weavers, was the most popular song in America.

Like many of the first 12-string players, Leadbelly played a Stella 12-string, which he tuned down to C. The lower pitch gave the guitar a rich, booming tone. Stellas were larger than the other 12-strings being made at the time, measuring 16 inches across the lower bout. The larger body also produced the louder volume that was so important in the pre-electric guitar world.

The ‘60s Revival

After

Leadbelly's passing, nobody immediately appeared to carry on the 12-string

tradition. It was as if musicians refrained from playing it as a sign of

mourning. Only a few guitarists, like Dick Rosmini, Fred Gerlach, and Pete

Seeger, kept the 12-string tradition alive. Seeger played it with he Weavers

and from college to college in what he called the “frightened ‘50s.” In

an unpublished interview with Andrew DeLory, Seeger said he considers his

role in spreading the 12-string as “one of the most important jobs I ever

did.”

After

Leadbelly's passing, nobody immediately appeared to carry on the 12-string

tradition. It was as if musicians refrained from playing it as a sign of

mourning. Only a few guitarists, like Dick Rosmini, Fred Gerlach, and Pete

Seeger, kept the 12-string tradition alive. Seeger played it with he Weavers

and from college to college in what he called the “frightened ‘50s.” In

an unpublished interview with Andrew DeLory, Seeger said he considers his

role in spreading the 12-string as “one of the most important jobs I ever

did.”

In the late ‘50s Pete Seeger's invention, the long-neck five string banjo, was the emblematic instrument of the folk scene. Popular groups like the Kingston Trio and the Limeliters reinforced the perception that if it didn't have a banjo it wasn't folk. But in 1963 two records came out that knocked the banjo off its throne. Ironically the first record was Pete Seeger's “We Shall Overcome,” which was recorded live at Carnegie Hall on June 8, 1963. Seeger used the 12-string's power and novelty to draw people to him like the buskers and medicine show hawkers did in the instrument's infancy. But rather than snake oil, Seeger was selling songs of justice and freedom. The extra volume and full sound of the 12-string guitar made it perfect for leading the sing-alongs that were an important part of the civil rights movement.

The other record to bring the 12-string to greater prominence was “Walk Right In,” by the Rooftop Singers, a trio that featured the right and left handed Gibson J12-45s of Eric Darling and Bill Svanoe. This old Gus Cannon song went right to the top of the charts, and the 12-string boom was on.

Soon the 12-string was everywhere. The Chad Mitchell Trio featured a young musician named James McGuinn was working up arrangements for a Judy Collins record when he got the idea to play what he called a “Bach-sounding riff” on the Pete Seeger song, “Turn! Turn! Turn!” A couple of years later he would remember this and use it in his new rock band, the Byrds.

Record companies rushed out quickie albums made by groups with names like the Folkswingers and the Folkniks. While these groups included guitarists like Howard Roberts, Glen Campbell, and Tommy Tedesco, they could hardly be called fold groups. And mainstream acts started going “folk” as well. Bobby Darin added a folk section to his Vegas act with the prolific McGuinn handling the 12-string duties. Even venerable singers like Marlene Dietrich got into the act, recording songs like, “Sag Mir wo die Blumen Sind (Where Have the Flowers Gone)” and “Paff der Zauberdrache (Puff the Magic Dragon).”

During this boom time, companies like Gibson and Martin that had ignored the 12-string in its infancy jumped up to cash in on its adolescence. Gibson introduced the J12-45 and B12-25, and Martin brought out the D12-20 and D12-35. Guild, a small company struggling to find a niche, found that it's slightly heavier models like the F-212 could be tuned up to standard pitch, and these instruments began turning up in the hands of musicians like Paul Simon and John Denver.

But before too long media saturation had rendered the acoustic 12-string a cliché. As the unplugged version faded from view, the new electric version, invented by Rickenbacker, took its place. George Harrison, the first musician to use the innovative instrument, started a run on Rickenbackers. Jim McGuinn changed his name to Roger and transferred the lessens he learned as an acoustic folkie to the electric 12-string and invented folk-rock. Songs like “Mr. Tambourine Man,” and Turn! Turn! Turn!” introduced a new sound whose permutations are still being explored. Led Zeppelin learned the lesson of mixing the melodicism of folk with the power of rock and came up with “Stairway to Heaven.” Tom Petty owes much of his style to the music the Byrds made in the “jingle jangle morning” of the ‘60s.

Kottke Steps In

Although

the acoustic 12-string guitar disappeared from the charts, it didn't die.

It retreated back to small clubs and coffee houses where players like Peter

Lang, Robbie Basho, and Leo Kottke began to explore the sonic possibilities

of 12-strings.

Although

the acoustic 12-string guitar disappeared from the charts, it didn't die.

It retreated back to small clubs and coffee houses where players like Peter

Lang, Robbie Basho, and Leo Kottke began to explore the sonic possibilities

of 12-strings.

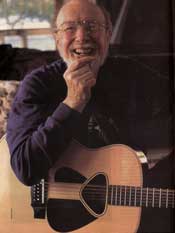

Kottke in particular is seen as the great 12-string innovator after Leadbelly. With a prodigious technique, he blended an unlikely mixture of blues, folk, classical, and jazz into a completely personal style. Throughout the ‘70s, Kottke kept the solo 12-string alive in an era that was more interested in disco dancing, stadium rocking, and punk sneering. He played a number of different 12-string guitars over the years, including instruments made by Gibson, Bozo, and Martin.

In the late ‘70s hand troubles forced Kottke to give up the 12-string and for ten years he didn't play one in concert. He began experimenting with different hand positions and picking techniques, and in the late ‘80s, he started playing a Taylor 55 mahogany 12-string. bob Taylor looks back on this event with pride, “Leo called me one day to say that he had stayed up until 4:30 in the morning playing my guitar, and starting with the show that night he was playing the 12-string in concert again. It was my guitar that got the 12-string king to play 12-string again!”

Over the years, the luthier and the musician worked together to create a guitar that would meet Kottke's demands, and in 1990 the Leo Kottke Signature Model was introduced. Bucking the trend for 12-string that could be tuned to E, the Kottke model was designed to be tuned down to C#, in effect making it a modern version of the old Stellas. It is also unique in being the first artist designed and endorsed 12-string guitar.

Kottke's success opened the door for other players. Two guitarists to take advantage of the new opportunities were Harvey Reid and Paul Geremia. Reid grew up listening to folk recording by musicians like the Kingston Trio and Pete Seeger. When he went out to buy his first guitar, he chose a 12-string Hoyer. Over the years Reid has honed his technique to the point where he is able to pick only one string of the paired strings, allowing him a much wider tonal range. On occasion he also plays the 12-string guitar banjo, an instrument made by the Deering Banjo Company and invented by West Coast musician Barry Hunn.

Paul Geremia was born in what he calls the Providence River Delta of

Rhode Island. He developed an interest I blues at an early age, particularly

the work of Blind Willie McTell. Hew was able to see many of the great

rediscovered blues musicians, like Son House, Skip James, Fred McDowell,

and Pink Anderson, at various folk and blues festivals in the early ‘60s.

Geremia has developed a style over the years that is based on the early

acoustic blues of players like Robert Johnson and Charley Patton, but is

still wholly his own. His main 12-string guitar is a Tonk Brothers model

made by Stella, similar to the one that Willie McTell played. Geremia has

been hailed by critics as one of the most accomplished guitarists working

in the acoustic blues tradition.

Into the MTV Era

Players like Kottke, Geremia, and Reid, who started playing in the ‘60s and ‘70s are becoming the grand old men of the 12-string. But to survive, the instrument needs new blood. The 12-string guitar is nowhere near as ubiquitous as it was in the ‘60s, but the instrument and its traditions do crop up here and there in the playing of younger musicians. Melissa Etheridge is perhaps the most visible artist currently playing a 12-string. Her powerful rhythmic attack on her Adamas guitar belies the image of the singer-songwriter as a purveyor of wispy, introspective ballads. Guy Davis is a young performer from New York who is reviving the 12-string style of Blind Willie Johnson and other prewar blues musicians. He's a strong guitarist and singer who likes to integrate his music into stage productions. In 1993 he performed off Broadway in the title role of the play, Robert Johnson: Trick the Devil.

In Nirvana's 1993 MTV Unplugged special, Kurt Cobain closed the show

with a haunting version of Leadbelly's “Where Did You Sleep Last Night?

In a New York Times article written after Cobain’s suicide, Eric Weisbard

describes Cobain and his friend Mark Lanegan listening to old Leadbelly

78s as kids. In 1990 Cobain and Lanegan recorded an unreleased EP of Leadbelly

songs. Cobain didn't record his version with a 12-string, choosing instead

to use a Martin D-18E, but his delivery of the song sometimes know as “In

the Pines” owes much of its brooding quality to Leadbelly. Perhaps a young

guitarist will trace the Cobain version back to Leadbelly's acoustic 12-string

take, and will be inspired to integrate the old instrument with a modern

sensibility and carry the tradition into the 21st century.