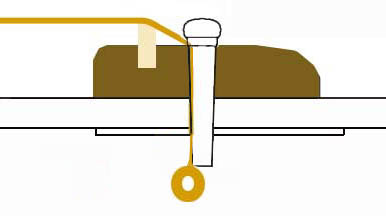

| Strings are supposed to go through the bridge, down below the top to

the inside, where the string balls engage the bridgeplate. Ideally the

string should hold there without benefit of a bridgepin, but we use bridgepins

anyway, just to help during restringing, anyway.

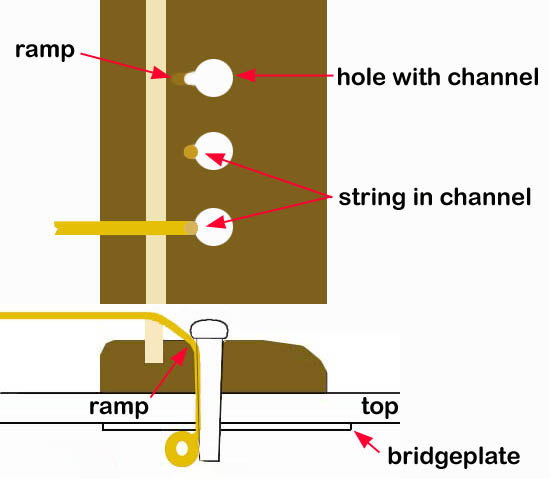

The hole fits the pin, and the string requires a bit more space to pass

through that hole alongside the pin.

|

| Here's the way it should be, ideally:

|

|

In any case, if the pin won't go down, it means something has to be done to accommodate that extra stuff. So you make a second string channel, and a bit of a ramp at the top of it to allow a smoother transition from the hole toward the saddle. Most of this channel and ramp needs to be at the top of the pin hole, since the pin itself is tapered. Ideally the bridgeplate is touched as little as possible, and the string

ball is pushed aside, as shown above.

|

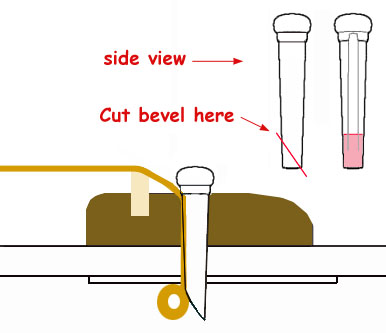

Sometimes the string ball catches on the bottom of the bridgepin, so

that when you tighten the string, it pushes up on the pin and sends it

flying.

|

A simple cure that often helps is to bevel the end of the pin with a file or a sharp knife to deflect the string ball to the right place. But often the best cure is to tweak that smaller channel so it fits the backwinding on the string and allows the ball to be out of the way of the end of the pin. This takes the right tools and some skill, because if it's overdone, the bridgeplate will be damaged and the ball may pull through it, then through the soft spruce, and finally to the bridge itself. This is a major cause of cracked and lifted bridges, and it also allows the winding to lay over the saddle, which has its own set of bad consequences. |