| Grain Runout

|

||

|

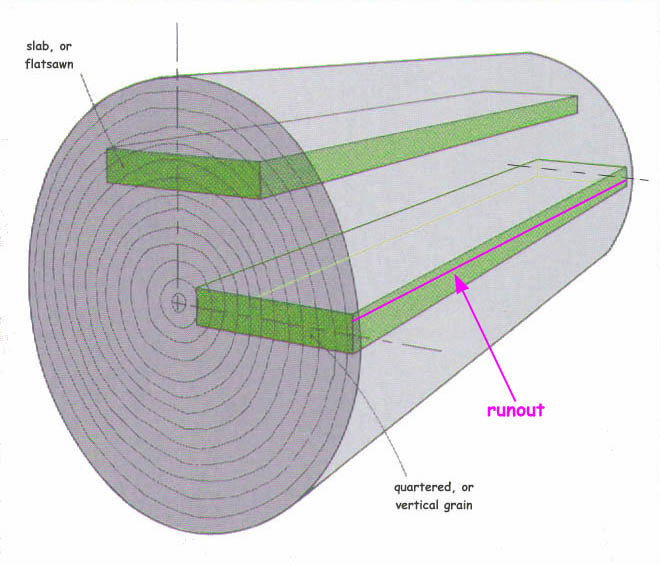

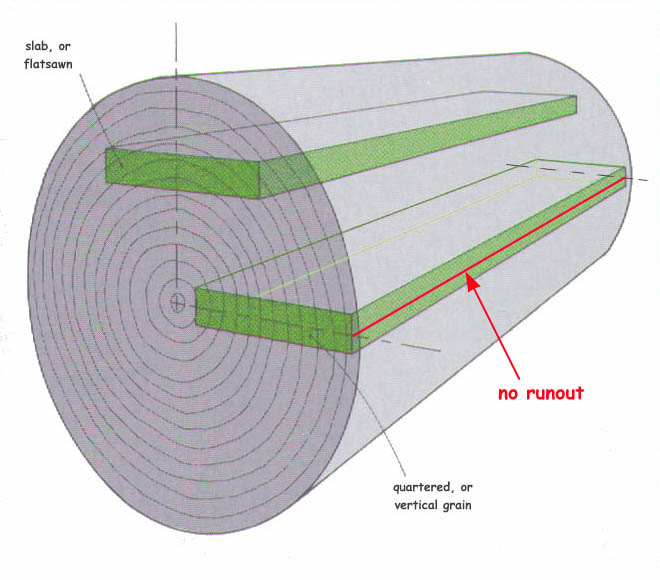

PH: We all know that the grain of wood runs along the length of the tree trunk, or branch. When a cylindrical log is cut into rectangular dimension pieces (green below), the grain may or may not run straight through the length of the piece.  The red line above is a cut through the wood. It can be either a saw cut or a split. In any case, if it precisely follows the actual grain, there is no runout. Wood being wood, however, the ideal situation sometimes does not occur.

If the cut is a bit off from that natural grain,

as in the sketch above, it reveals what is known as "runout." This sort

of thing happens when you saw the wood. It's nearly impossible to

do by splitting or riving the wood. Even if it is sawn, it is still cut

on the quarter, but the result is that the light striking the wood will

reflect differently.

|

||

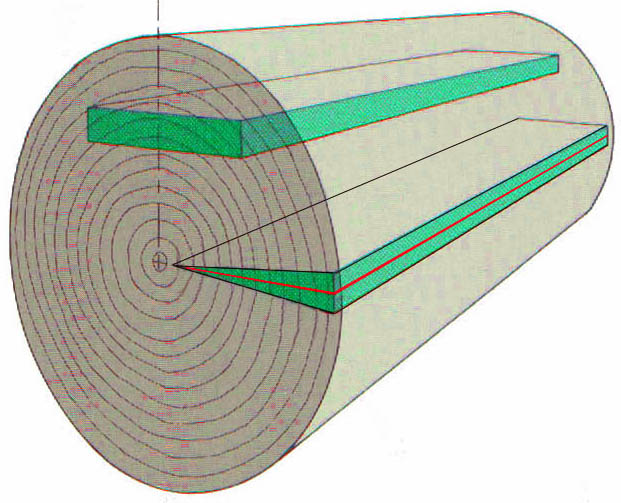

| Here's a way rived wood can be quartersawn

and then bookmatched:

The wedge at right is what's known as quartered, or quartersawn. If you split this wedge precisely down the center and open the resulting two pieces like pages of a book, such that the outside face of each wedge is pressed together, the pieces are said to be bookmatched. Like this:

The narrower edges at the outside of the top were once in the center

of the tree.

|

||

|

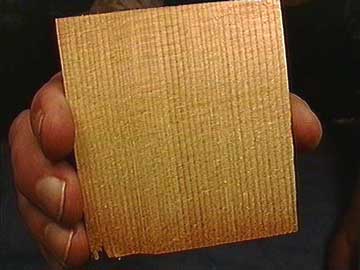

Now, here are some images and accompanying

text from Frank Ford's FRETS.COM

Illustrated Glossary, with a bit of my commentary (in brown) farther down.

Here's a piece of spruce:

It's easy to see how the grain runs in this

dimension. It's quite straight and true, just like an ideal instrument

top.

|

||

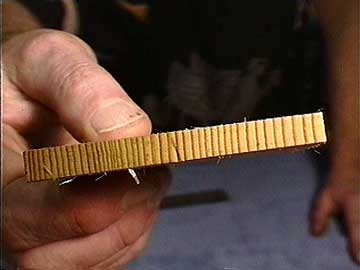

| Here's the end of the same piece:

This is what is called "vertical grain." You

can see from this cut end that the grain lines are almost straight up and

down in relation to the flat face of the board. There's no question how

this wood will split if I break it between these grain lines. It will split

directly from one end to another right along the grain.

|

||

| Let me take a quick break to introduce you

to two simple tools:

(*This tool's English name is "froe." And to cut

with it is "to rive," hence the term "riftsawn," which means sawn along

the natural line that could have been riven or split.)

|

||

| Now here's the remaining side edge of that

spruce board:

|

||

| Let me give it a whack:

Now, it's really easy to see the grain direction:

This is, by the way, how the very finest instrument wood is cut. To make absolutely sure that there's no grain runout, the tops of instruments are sometimes cut from "split billets" to ensure straight, uniform grain with no runout. |

||

|

Let me split this other piece, which also has the grain running perfectly vertical along the face and through the length:

I couldn't tell that there was grain runout

by looking at the edges, but spitting is a dead giveaway.

|

||

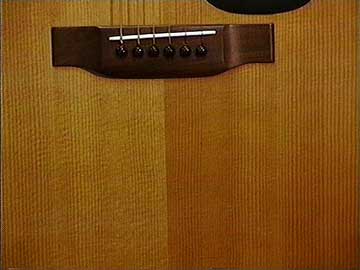

Here's a classic case of runout on a finished

guitar top.

|

||

PH: one small thing to add here—this effect can also be caused by "bookmatching" reasonably well-quartered spruce pieces with grain that is not 100% vertical, and whose grain opposes like this: \\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\|//////////////////////////////// Each side will reflect light differently, giving

the same effect as wood that's not riftsawn, or which has runout.

|

||

| Frank: OK,

why all the fuss about grain runout?

Well, for one thing, wood with no runout is stronger. If it is really stressed hard it won't break as easily because the grain can't split off the edge. Severe grain runout is bound to have an effect on the vibrational characteristics of a top as well as an effect on the strength. I don't pretend to be able to discuss the theoretical differences in tone, but in a few cases I've actually seen tops fail structurally because of grain runout. In those few instruments, the grain runout was astoundingly bad, say around 30 degrees off parallel. The guitar pictured above happens to sound GREAT, and shows absolutely no structural difficulties despite its 29 years (as of 2005) under string tension. The matter of grain runout is largely a cosmetic one, and most builders try to avoid runout if possible. |

||

| To Frank's Glossary | To Frank's Index Page | To my index page | To my site map |