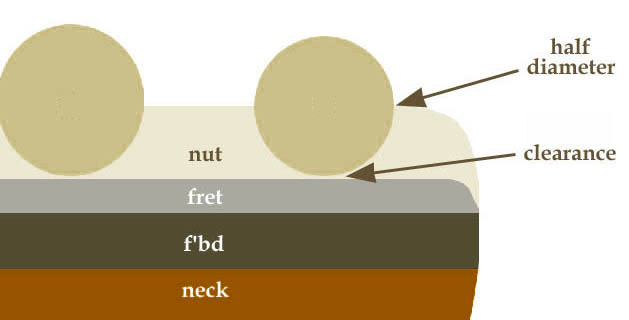

| Nut slots ...with principles that apply, as appropriate, to bridge slots as well Here's a gnat's-eye view at the face of a nut as seen from the leeward side of the second fret. The slots for these two strings are cut so that they completely support the string.

The sketch above

relates to fretted instruments, but the basic

principles are no different for violin family and

other unfretted instruments. I'll try to explain the

clearance in a minute. Here's an idea of

how it works on a bass:

Here's a

shimmed-up mess of a nut that has all the problems:

These slots are all too deep, but the B is still so high it doesn't play in tune, so someone shoved a piece of ebony under it to try and correct the intonation. Big "Ugh" for this one. People often

comment on certain strings (e.g., mandolin A

strings, guitar G strings) being more troublesome,

always seeming to go out of tune during play.

Mandolin A's are always the most troublesome because

they have to make compound bends from the nut: back

as well as to one side. And the length from the nut

to the post being the other important factor. And

being plain strings, they tend to bind if the slots

aren't cut right. (The D's, being wound, tend to

refine their own slots.) When you tune, you always tune up to a note, never down, right? Right. It's about friction in the slot. And with a poorly

cut nut, when you tune up, the tension on the length

of string between the nut and the string post is

greater (per unit of length) than the part you

actually play, that's between the nut and the

bridge. After getting the pitch just right, a bit of

actual playing works the string, making the tension

on both sides of the nut equalize, and voilà: you're

out of tune in mid-phrase. It has nothing to do with

the tuning machines, which people just love

to blame, but everything to do with setup,

particularly how precisely the string slots at the

nut are cut. A quick word

about creaking guitar G strings: this issue is

fading as elephant ivory nuts are fading. Bone is

superior to ivory for a nut material because it's

harder and burnishes better. Ivory is soft and

actually registers the imprint of string windings.

That irritating creak is the sound of the windings

skidding over grooves impressed inside the nut slot.

Once again: setup is everything. (You can resurface

string slots in an ivory nut by inlaying bits of

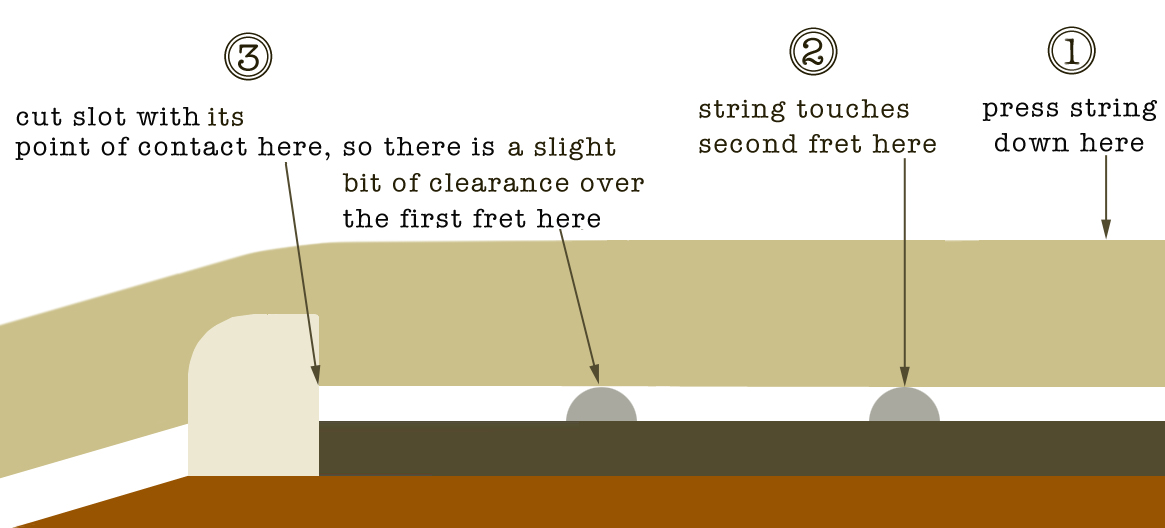

with pearl or bone, if you like.) How do you easily determine the ideal height of the string slot in the nut? OK, start with ⓵:

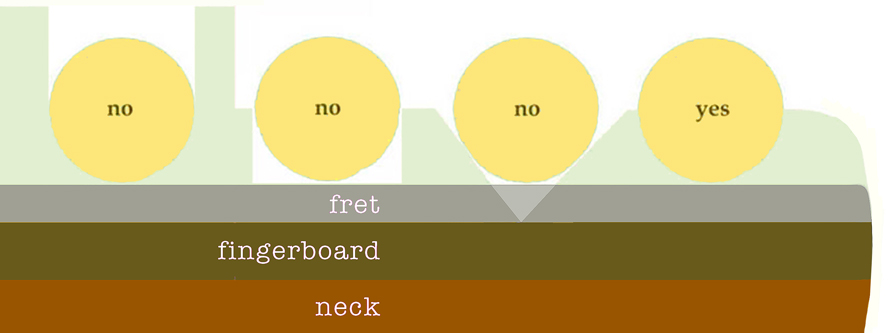

The sketch below

illustrates how - and how not - to shape a slot for

any string. Left: like the

messy nut above, the nut material is too high. You

need only enough to support half the diameter of the

string. Anything more is just in the way. When the

string is way below the top of the nut, you have

great difficulty telling whether it's seating

properly. Next: a slot that's cut with a saw has a roughly flat bottom and also affords poor acoustic coupling. Saws seldom match the precise width of the string, which can roll side to side in the slot. Next: strings

will work their way down a v-cut, often bottoming

out on frets (or the board, as the case may be with

fretless instruments). The signal transfer is

compromised because of the limited contact, and the

string sizzles on the fret or the board. They also

tend to bind and squeak. They can ruin your day. Right: the slot

really fits the diameter of the string, the nut

material does not go above the halfway point of that

diameter, and leaves the string a trace of clearance

above the fret or the unfretted board surface.

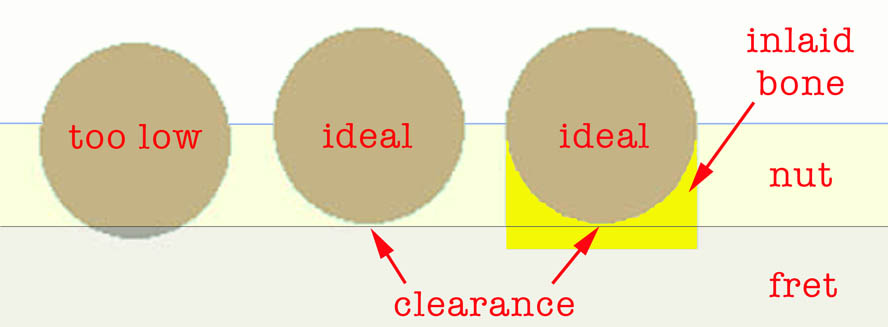

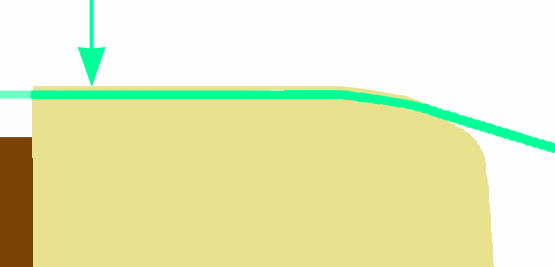

How much is a trace? I'm reluctant to assign a measurement—it's very little. You can still see a bit of light. If you hold any string down on any fret of a well set up instrument, you'll see that same preferred clearance at the next fret up. Before going further, here's how to

correct a string slot that's too low. Often it's

wiser to repair a blown slot than it is to replace

the whole nut. Quick fixes like some kind of dust

(bone, acrylic, baking soda) with superglue are

really temporary. It takes little more effort to

implant a little patch of bone (or even pearl)

into the nut and recut the slot. It's as good as

the original, and if done well, is quite

invisible.

Trim and dress

the nut as if it was new and uncut, then cut the new

slot.

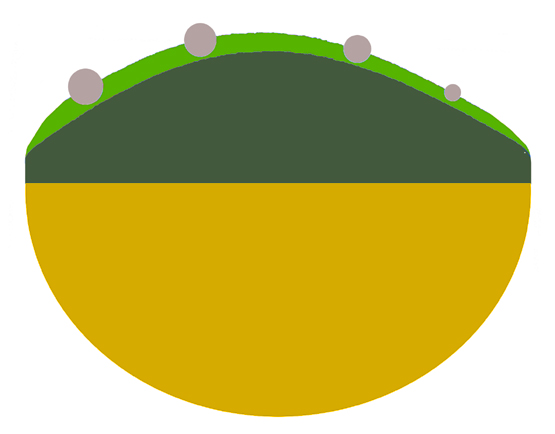

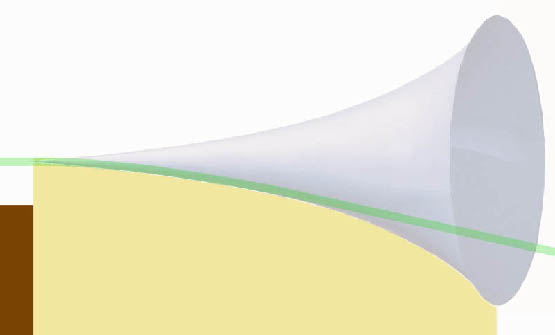

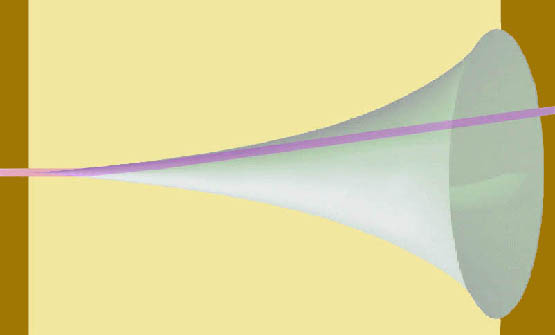

I prefer to shape my slots in the shape of a horn's bell:  The point of this

is to offer a smooth surface for the string to

travel from the tuning machine to the critical point

of final contact at the front of the slot, where it

is held firmly to define the end of the vibrating

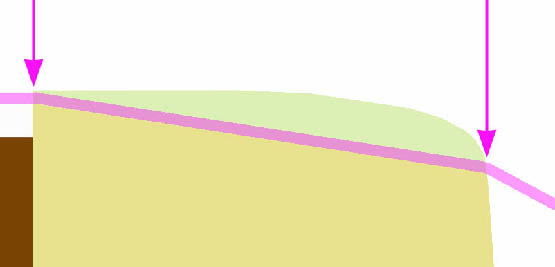

string length. Strings have to make a compound bend at the nut, and to make tuning easiest while ensuring complete firm contact at the front of the slot, this horn bell shape makes certain the string glides smoothly, no matter the angle of approach. Here's a treble side view:

The bell here is imaginary. The nut is in yellow, the fingerboard is dark brown. The string is the green line, and the tuning machines are off to the right somewhere. Notice that the string connects with a smooth curved surface, no corner or edge. Whether the string is coming from the top or the bottom of the string post, it will slide smoothly into the nut slot. The string is in complete contact with the front 30% of the nut. There's plenty of substance there to keep the string from sawing its way deeper into the bone. Here's the same slot seen looking straight down from above:

The string's other curve, from, say, the farthest peg on the bass side of the headstock, also elides with the inside of the bell-shaped slot, guided gently and directly to the front where it's held firmly by its own tension inside the confines of a well cut slot. If the slot isn't

properly angled back, several problems can arise. If it's too flat

(some repair books actually advocate this!) the

string soon wears away the front of the slot and the

functional point of contact is as much a 40% of the

width of the nut back from the front edge,

which can cause the note to ring poorly (because

it's vibrating along a surface, not held to a point)

and perhaps cause intonation problems. This is bad:

If the slot is

angled back, but left a straight line, it will bind

on the back edge, and the front edge will wear down

from playing and the string is at risk for sizzling

on the first fret or on the surface of the board.

This is also bad:

The precise shape

of the slot at the front edge is extremely important

for sound quality, stability of the setup, and

intonation. More on bridges

in due time, but the principles here apply to bridge

slots on the viol and violin families, guitars,

mandolins, and so on. |