Details -on bracing -on rosettes -on finishes Musicians

Background

information

the rest of

the site

Email:

click

here

|

People often ask questions about the

"arching"

or doming of the tops on Selmer guitars - about the bracing, the bent

top,

and so forth. Here’s an exchange I had with Sam Powrie, of

Adelaide,

Australia, on this subject. We also talked about woods, but let's just

put out the bracing conversation first.

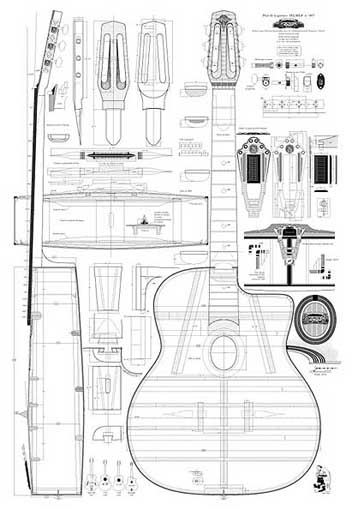

SP: I want to ask someone how Selmer got the bend across the guitar soundboard? Was it a straight saw cut part way through the sound board combined with judicious bending? I note that there's a lateral arch as well which is an added complication I guess. PH: There was a bend in the Selmer tops, similar to the fold, or "crank," across the top and behind the bridge, in the style of Neapolitan mandolins. Since the engineering of Selmers was so close to Neapolitan mandolins, this assumption is understandable, but Selmer tops were not bent quite the same as the mandolins. 1) The halves of the tops on the later ones (non-gut strung) were pre-bent before they were joined. This is shown in François Charle's book (page 162 of the English edition), but you really have to study the photo of the jig to see what I am talking about. Even his blueprint of the jazz model shows a sharp crease, which is slightly misleading, since real Selmers have a bulgy smooth dome, not a crease. Some evolved a more exaggerated hump there due to the longitudinal compression of the strings and the placement of a transverse brace just behind the bridge. But fresh out of Mantes-la-Ville, their tops were simply domed. No pronounced fold or "crank," as one sees on Neapolitan mandolins, was ever originally there. 2) There were some Japanese-made Maccaferri guitars (the Suzuki/Ibanez jobs instigated by Maurice Summerfield and Mario Maccaferri in the 1970s) that did have an authentic cranked top, but these were a much later Maccaferri design, done to his specs when he lived then in New York. 3) The Selmer Maccaferri steel string tops all started as a flat sheet of spruce, with a gentle bend in the top accomplished by heating over an iron. They were glued to transverse (ladder) braces that were well curved, just like Neapolitan mandolins. Then the top was glued all around to the body's sides, which were on a single plane. This exerted some tension on the wood because, though the side edges already had their downward curve, the truncated cylinder-shaped top had to be pulled down to the neck and heel blocks. So the result was a more-or-less even dome, leaving the formerly flat sheet of spruce under tension. SP: Has anyone written on this to your knowledge? PH: Maurice explained it in detail in his lecture at the GAL a few summers ago, but unfortunately that lecture has never been published because the folks taping the lecture screwed up and forgot to turn the machine on. We (meaning Maurice, François Charle and/or I) also touched on it in several articles over the years. The matter of (for lack of a better term) tensioned flat tops has gone through cycles of understanding and obscurity over the years. The old mandolins from Naples had them, an obvious adaptation to steel strings which came in during the 19th century, replacing gut strings. The crisp bend enabled luthiers to put a real dome to resist the downward pressure of the steel strings. The leap to guitars was an obvious one, especially in the hotbeds of Italian lutherie, like Mozzani's school, of which Mario Maccaferri was a proud product. Bouzoukis and biwas have them as well. It's axiomatic that stiff woods make better sounding tops. Take a stiff wood and force it into shape under tension, and you multiply that stiffness, with a concomitant effect on tone. Building tops under tension was used to great advantage by the Larsen Brothers, who worked in Chicago many years ago, on their Maurers, Stahls, Prairie States, Euphonons, and so forth. Anyone fortunate enough to hang out with those instruments knows that after 75 years, they still have that vital, bright "new guitar" sound, while all their vintage classmates have a distinctly played-in sound. Stefan Sobell also uses this principal on his flattops. Inspired by the Larsens, Dana Bourgeois was the first guy in recent times to sound the charge for this construction technique, and uses it in his guitars. As a consultant to Gibson when they first got their Montana shop going, he got them to do it too. Like Selmers, the flat tops are glued (in a dished form) to curved braces. Santa Cruz Guitar switched over to this awhile back, and I asked my friend Adam Rose, who's the shop manager for SCGC, how he quantified the difference. He described it as yielding notably more volume and perhaps a bit less complexity. I thought this was an interesting observation. Sobell guitars, however, have a very complex sound, but I would be reluctant to make the claim they were particularly loud guitars at all. But one cannot liken his doming to the one SCGC is using either - it's much more pronounced. I'd like to make a small plea here for some clarity in terminology: ARCHED TOP means a top (or back, for that matter) carved from a block of wood. The final shape is arrived at simply by subtracting wood, and the final multiple-curved profile in wood which is at rest. Add to this that many makers, following the cue of violin making tradition, glue in braces or bars with a greater arch than the surface they are glued to, which adds tension. PRESSED TOP Some archtops, mostly older budget items, are arrived at by placing a flat sheet in a heated two-part mold and pressing them into an arch. Good examples are all old Harmonies, low-end Gibsons and Martins (L-50 and the R series, respectively) and most cheap violins, like those from Korea, Cleveland, and Sri Lanka. These look like archtops, but because they are heat pressed, they sound different. There is a current school of violinmakers who use what they call PLATE BENDING, which is starting with rather thick, joined flat sheets of wood, pressing them with heat into a rough arch, then doing final graduation - a hybrid between pressing and carving. Proponents claim this is how the Cremonese masters got their sound, despite the fact that no Strad or Amati bears witness to this technique. The results of this technique are not universally acknowledged, but a lot of makers follow the technique enthusiastically. DOMED TOP is the term I personally prefer for tops that are flat sheets that are put under tension cold - so the cell structure and grain integrity are not breached. It's a sheet of tonewood under tension. Pressed tops are not under tension, which was relieved by heating and relaxing the wood as it was shaped. Some folks properly refer to a domed top as a flat top with radiused braces. There are other terms as well. FLAT TOP is basically the common standard in Spanish and American lutherie traditions - flat braces glued to a flat top, no tension except that which the string tension imparts. It devolves from lute making tradition, it's very old. Many of these tops become domed, in the general sense, by years of being under string tension. Stefan Sobell, whose guitar tops have a very pronounced dome refers to them as flat tops. Stefan also does authentic carved top guitars, and chooses to make the distinction thus. One glance at his guitars, or at a Dupont or Selmer, and you know it's not a flat top in the traditional sense. It's worth noting that most archetypal flat top guitars, including OM-28s and classical guitars, have traditionally had a domed back, more for purposes of structural strength (rigidity and resistance to crushing) than anything else. In conclusion, Selmer guitars are not archtops (even though

their tops

have an arch). They're not flattops (let's leave that term for

steelstring

folk guitars like Martins and so on). They're not pressed (no heat).

They

do

have a domed top - essentially a flat sheet of wood under tension. Have a topic you think is worth some discussion

here?

This page ©

1999-2011 |